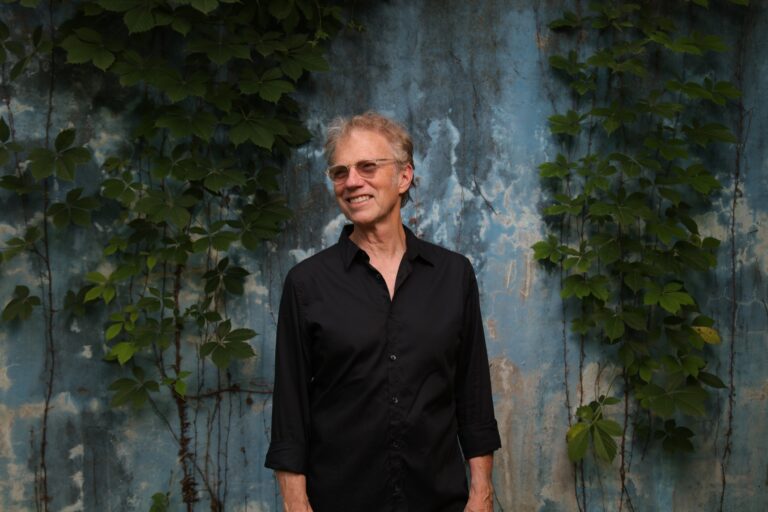

Randall Bramblett is a lifer. For decades, he’s explored the deep corners and outer orbits of American roots music, creating a southern sound that’s every bit as eclectic as its maker. That sound reaches a new milestone with Paradise Breakdown, the thirteenth record from a musician hailed as “one of the South’s most lyrical and literate songwriters” by Rolling Stone. The album finds Bramblett taking stock of past and present, embracing all the contradictory elements — love and loss; joy and disappointment; nostalgia and mortality — of a career dedicated to creation.

“I’ve had the realization that this particular life isn’t gonna go on forever,” says the 70-something musician, who launched his solo career with 1975’s That Other Mile while moonlighting as a multi-instrumentalist for acts like Gregg Allman and Sea Level. “It’s true that everything ends, but things are still really beautiful, too. I’m healthy. I’m happy. I have a lot to be grateful for.”

Bramblett captures that paradox with tracks like the album’s sunlit opener, “Fire Down in Our Souls” — a funky love song rooted in groove and grit, its chorus stacked with soulful vocal harmonies — and the mean, murky “Down in the Wilderness.” “That’s my kind of song: deep and dark,” he says of the latter recording, which makes room for ghostly electric guitar, atmospheric chords, and a tense pulse. Things get psychedelic during the song’s bridge, where Bramblett’s upright piano leads the way into outer space. At its core, though, this is earthbound music — the kind of electrified soul-funk and dive-bar R&B that feels raw and broken-in, rooted in the storytelling chops of a man who’s spent much of the past half-century in the recording studio and on the road.

Bramblett tracked half of the album in East Nashville. He’d been coming to the city for decades, not only to play his own shows, but to record some of his own earlier albums for New West Records, as well. Along the way, he’d watched other artists record many of his songs. Bonnie Raitt opened her Grammy-winning album Slipstream with his composition “Used to Rule the World” in 2012. The Blind Boys of Alabama covered his song “Almost Home” on their own Grammy-nominated record several years later. Blues legend Bettye LaVette took things a step further, recording 11 different Bramblett compositions on her Grammy-nominated record LaVette! and dubbing him “the best writer that I have heard in the last 30 years.” Paradise Breakdown proves that Bramblett has plenty of material for his own projects, too. Teaming up with legendary instrumentalists like Tom Bukovac, Steve Mackey, Nick Johnson and producer/drummer Gerry Hansen, he cooked up up his own melting pot of urban swamp-soul and modern roots music in the East Nashville studio. Once those sessions wrapped up, he headed back to his adopted hometown of Athens, Georgia — a four-hour drive from his birthplace of Jesup — to finish the record with familiar partners like Seth Hendershot, A.J. Adams, Tom Ryan and Nick Johnson. The result is a mix of organic performances and electronic textures: an album built for roadhouse dance floors, dark lonely corners, and the long ride from past to present.

Balance. It’s something Bramblett has always emphasized not only in his music, but in his career, too. He’s one of the unsung heroes of modern-day American music, composing his own albums one minute and playing a supportive role in the careers of other musicians — including Steve Winwood, Widespread Panic, Chuck Leavell, and Marc Cohn, all of whom have cherry-picked Bramblett to be a member of their touring bands — the next. Listen to his voice, a gravelly baritone that can bend its way around melodies like well-worn leather, and you can hear the evidence of a half-century’s worth of shows, from acoustic performances to amplified, full-band gigs. Paradise Breakdown offers more than the soulful, sobering reflections of a road warrior who’s willing to take a look at the blacktop stretching out behind him, though; it’s also a snapshot of a man still in motion. There’s still plenty of blacktop up ahead, and Bramblett is ready to chase it down, dedicating himself to the long haul. “I’m still working with my friends, making my own records and playing exciting shows,” he says. “There’s always this sense of newness to it all that I love.”

Maybe this — an historic career that’s still unfolding, reaching new milestones with each passing year — is what paradise looks like, after all.